you are correct, here. By "Valentinian Mythicists" I mean precisely, in the title and in the rest of the discussion, Valentinians who placed a crucified Christ in heaven, more precisely between the "pleroma" (=upper heavens) and the lower heavens. In the place called by Carrier (& Carrier's fan) as "outer space". Hence I should use, for sake of clarity, a more strict terminology, to distinguish Valentinians from Paul.GakuseiDon wrote: ↑Tue Aug 27, 2019 1:36 am Don't you call Valentinians, who believed in an earthly Jesus, "mythicists"? Why can't Paul also, under mythicism, believe in an earthly Jesus? This is more about understanding your terminology. See the title of this thread, where you refer to "Valentinian mythicists".

I think and believe that:

1) Paul was only a mythicist: the his Jesus is only one and he is always and only in heaven.

2) The Valentinians were historicists (we all agree about that, I would hope) but they were also mythicists: they believed that another Christ, one distinct from the earthly Jesus, was crucified in heaven.

Hence, when I use the term "Mythicist Valentinians", I am not denying the evident fact that the Valentinians were historicists: only, I am claiming that their system assumed two crucifixions, one earthly and the other celestial. Both with the same degree of reality.

Because Valentinians broke the silence about an earthly Jesus. While Paul didn't break the his silence about the earthly Jesus. At least, according to modern mythicists.Why couldn't Paul have been a "Valentinian" historicist?

ok, bravo, you will agree with myself that the way by which an earthly crucified Jesus was doubled by another Christ crucified in heaven, under a particular late Gnostic sect and under the historicist paradigm, is a different question. But the my goal here is to persuade you, possibly, that there is clear, strong and precise evidence of a Valentinian belief about two distinct crucifixions: one earthly and another celestial (=in outer space).That is a seriously silly statement, Giuseppe. The apparent development of the Christ Myth (in its broader meaning) is from a man (as seen in Paul and the Gospel of Mark), to a virgin-born Son of God, to the pre-existing Logos/Son of God, to the status of God Himself. As Jesus' status grows, so the explanations regarding his origins expands and become more complex. This can be seen in any fan fiction. The Second Century was full of ideas about the origins of Jesus; the ones that didn't make it into orthodoxy became heresies. Many of those ideas developed long after Christianity had become historicist, even by mythicist time-frames.

precisely there you are wrong.

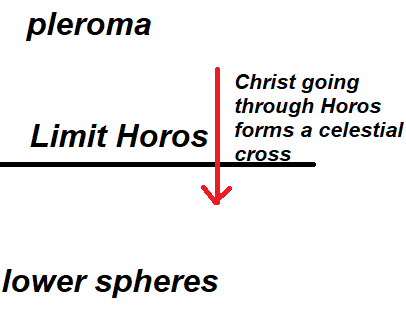

Again: I'm not reading Horos as symbolic, but the superior Christ being stretched out through Horos-as-boundary as a symbolic crucifixion.

This is historicity:

This is not historicity and this is not symbolism:

..since Teetullian himself specifies the absolute degree of reality of the celestial crucifixion just described above:

"substantial" is the exact contrary of "symbolic".

But then the balance seems to be inclined more towards the questioning of the same historicist belief:

"all things" are an earthly Jesus, an earthly cross, an earthly Christian, GDon and Giuseppe. The Valentinians, in reason of their belief in two crucifixions, are moved, according to Tertullian, to postulate a correspondent celestial thing for any earthly element: an earthly GDon becomes the "mere image" of a celestial GDon (=in outer space), an earthly crucified Jesus becomes the "mere image" of a celestial crucified Jesus (=in outer space), and so on. This is dangerously similar to a questioning of the same historical reality of a GDon, of a Jesus, and so on.

McGrath doesn't say the entire truth.Here is what you quoted from Dr McGrath:

"The obvious question, of course, is whether one thinks the Valentinian reading of Romans is what Paul intended. If not, then this doesn't really provide anything that would support mythicism. Indeed, even if one thinks that Valentinus preserved precisely what Paul meant and taught, that still wouldn't help mythicism, since Valentinus thought Jesus had appeared in history."

I agree with the highlighted part. How about you?

The entire truth is the following:

But Valentinus thought also that another Christ, distinct from the Jesus crucified in history, was crucified really (and not symbolically) in outer space.

Is it clear now?