St Mark, the early Alexandrian church and the Cow Pasture

And when those that believed in the Lord were multiplied, and the people of the city heard that a man who was a Jew and a Galilean had entered the city, wishing to overthrow the worship of the idols, their gods, and had persuaded many to abstain from serving them, they sought him everywhere; and they appointed men to watch for him. So when the holy Mark knew that they were conspiring together, he ordained Annianus bishop of Alexandria, and also ordained three priests and seven deacons, |145 and appointed these eleven to serve and to comfort the faithful brethren. But he himself departed from among them, and went to Pentapolis, and remained there two years, preaching and appointing bishops and priests and deacons in all their districts.

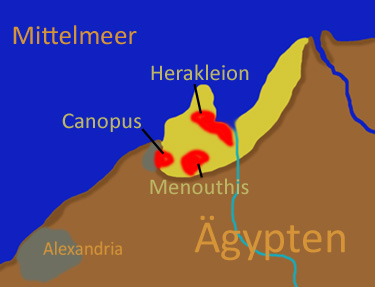

Then he returned to Alexandria, and found that the brethren had been strengthened in the faith, and had multiplied by the grace of God, and had found means to build a church in a place called the Cattle-pasture (Τὰ Βουκόλου) near the sea, beside a rock from which stone is hewn. So the holy Mark greatly rejoiced at this; and he fell upon his knees, and blessed God for confirming the servants of the faith, whom he had himself instructed in the doctrines of the Lord Christ, and because they had turned away from the service of idols.

But when those unbelievers learnt that the holy Mark had returned to Alexandria, they were filled with fury on account of the works which the believers in Christ wrought, such as healing the sick, and driving out devils, and loosing the tongues of the dumb, and opening the ears of the deaf, and cleansing the lepers; and they sought for the holy Mark with great fury, but found him not; and they gnashed against him with their teeth in their temples and places of their idols, in wrath, saying : «Do you not see the wickedness of this sorcerer?»

And on the first day of the week, the day of the Easter festival of the Lord Christ, which fell that year on the 29th of Barmudah, when the festival of the idolatrous unbelievers also took place, they sought him with zeal, and found him in the sanctuary. So they rushed forward and seized him, and fastened a rope round his throat, and dragged him along the ground, saying : «Drag the serpent through the cattle-yard! (Σύρωμεν τὸν βούβαλον ἐν τοῖς Βουκόλου) » But the saint, while they dragged him, kept praising God and saying : «Thanks be to thee, O Lord, because thou hast made me worthy to suffer for thy holy name». And his flesh was lacerated, and clove to the stones of the streets; and his blood ran over the ground. So when evening came, they took him to the prison, that they might take counsel how they should put him to death. And at midnight, the doors of the prison being shut, and the gaolers asleep at the doors, behold there was a great earthquake and a mighty tumult. And the angel of the Lord descended from heaven, and entered to the saint, and said to him : «O Mark, servant of God, behold thy name is written in the book of life; and thou art numbered among the assembly of the saints, and thy soul shall sing praises with the angels in the heavens; and thy body shall not perish nor cease to exist upon earth». And when he awoke from his sleep, he raised his eyes to heaven, and said : «I thank thee, O my Lord Jesus Christ, and pray thee to receive me to thyself, that I may be happy in thy goodness». And when he had finished these words, he slept again; and the Lord Christ appeared to him in the form in which the disciples knew him, and said to him : «Hail Mark, the evangelist and chosen one!» So the saint said to him : «I thank thee, O my Saviour Jesus Christ, because thou hast made me worthy to suffer for thy holy name». And the Lord and Saviour gave him his salutation, and disappeared from him.

And when he awoke, and morning had come, the multitude assembled, and brought the saint out of the prison, and put a rope again round his neck, and said : «Drag the serpent through the cattle-shed!» And they drew the saint along the ground, while he gave thanks to the Lord Christ, and glorified him, saying : «I render my spirit into thy hands, O my God !» After saying these words, the saint gave up the ghost.

Then the ministers of the unclean idols collected much wood in a place called Angelion, that they might burn the body of the saint there. But by the command of God there was a thick mist and a strong wind., so that the earth trembled; and much rain fell, and many of the people died of fear and terror; and they said : «Verily, Serapis, the idol, has come to seek the man who has been killed this day».

The Martyrdom of Pope Peter (c 311 CE)

Martyrdom of Petros, bishop of Alexandria (BHG 1502a)

Summary (following the chapter divisions of Devos):

§ 1: In the reign of the lawless emperor Diokletianos, there is a great storm and uproar [i. e. persecution of Christians]. At that time a pious and virtuous man, Petros, ascends the episcopal throne of Saint Mark the Evangelist in Alexandria. When his fame reaches the emperor's ears, five so-called tribunes are sent to capture Petros and bring him to Nicomedia.

§ 2: When the tribunes reach Alexandria, they arrest Petros as he is leaving the church after a service. The bishop is calm and goes willingly, adding merely that 'let the will of God be done'. However, seeing their bishop being taken away, the people of Alexandria rise against the tribunes, shouting protests and throwing stones at them. Unable to proceed, the tribunes give orders for the bishop to be held in the local prison while they report back to the emperor. The people pray night and day outside the prison where Petros is held.

§ 3: Diokletianos is greatly angered at these events, and sends the tribunes back with orders to bring him the bishop's head and to strike down any Christians who offer resistance. However, when they attempt to extract Petros from the prison, they are prevented by the people, of all ages and including virgins and monks, who are camped outside and insist unanimously that the bishop will only be removed after they have all been slain first. The tribunes make plans to enter the prison by force and slay any who resist.

§ 4: Having learnt of this, the heretic Areios is frightened that with the removal of Archbishop Petros he will remain excommunicated (which he had been due to his deviant views concerning the Holy Trinity), and, gathering many clerics, begs them to go to the prison to plead with Petros for him to be received back into communion. The clerics, thinking this to be a pious act, duly go to pope Petros and, after kissing his hand, request that Areios' excommunication be lifted.

§ 5: Archbishop Petros, however, upon hearing this raises his hand and affirms that Areios will be eternally severed from the glory of God. All present are frightened and silent, for they understand that Petros has spoken these words out of some kind of revelation [ἐκ πληροφορίας τινος]. Petros then takes two presbyters, Achillas and Alexandros, aside and reveals to them that after his martyrdom, he will be succeeded by Achillas, who in turn will be succeeded by Alexandros. He asks them to not think him unmerciful, since he did not anathematise Areios out of a personal conviction [οὐ ... ἀπ' ἐμαυτοῦ].

§ 6: Petros reveals to the two priests that the previous night he had seen a vision: a twelve-year-old boy, his face glowing with light, wearing a sleeveless (or short-sleeved) tunic (κολόβιον), which was split vertically in two at the front; with his hands the boy held the tunic's halves together, covering his nakedness. Petros cried out, asking 'Lord, who has torn your tunic'? and received the reply 'Areios tore it'. After this, the Lord told Petros not to receive Areios back into communion, and to instruct his successors, Achillas and Alexandros, to do likewise; for Petros himself was to be martyred.

§ 7: Petros reminds his fellow clerics that all his life he had wandered from place to place under harassment by the idol-worshippers, from Mesopotamia and Syria to Phoenicia, Palestine and various islands, writing in secret and encouraging the persecuted Christians. He had worried over the incarcerated bishops Phileas, Hesychios, Pachomios and Theodoros, and wrote them letters of exhortation from Mesopotamia, giving thanks to the Lord when they were martyred. He reminds his audience that until the present day, there had been six-hundred-and-sixty martyrs there (in Alexandria/Egypt?), and of the evils caused by Meletios [sic] of Lycopolis in the Thebaid, who caused a schism in the church.

§ 8: Finally, Petros reveals to Achillas and Alexandros that he is ready to suffer martyrdom, and that they will not see him again in the flesh; his conscience is clean, for he has revealed to them his vision and has given them sufficient instruction for the future. He prophecies that after his death certain clergymen will speak twisted words and will cause another schism like that of Meletios. He also reminds the future bishops of their illustrious forebears on the episcopal throne of Alexandria: of the dangers faced by his immediate predecessor Theonas because of the pagans; of the great Dionysios, who spent time in hiding during the persecutions, and who was also vexed by the heretic Sabellios; of Herakles [sic] and *Demetrios (S01935), who had faced the insanity of Origen, who caused schisms that are still active in the church (καὶ αὐτοῦ σχίσματα βάλλοντος ἐν τῇ ἐκκλησίᾳ τὰ ἕως σήμερον ταραχὰς αὐτῇ ἐπεγείροντα); of all the bishops before them, and of their labours in caring for the church of Christ. Finally, he entrusts his successors to the hands of God.

§ 9: Petros prays and says goodbye to Achillas and Alexandros, who weep at the thought of not seeing him again in the flesh. The archbishop then speaks words of encouragement to the rest of the clergy and the laity, and dismisses them with a prayer. Taking their leave, Achillas and Alexandros reveal in secret Petros' words to the sincere among the clergy; it is generally recognised that his words against Areios must be due to divine revelation. The wicked Areios, however, keeps up his pretence, hoping to influence Achillas and Alexandros.

§ 10: After learning of the tribunes' plan to extract him through force, Petros, fearing a bloodbath, concocts a plan to surrender himself and spare the crowd. He sends a secret message to the tribunes, inviting them to come at night to the southern wall of the prison (away from the door where the people hold watch), and promising to signal to them his location by knocking from the inside; the tribunes will then be able to dig a hole in the wall and take the archbishop away without anyone being the wiser. The plan is executed successfully, with the help of a strong winter wind that miraculously starts to blow in the night, masking the sound of the wall being cut open. Thus Petros surrenders himself like a good shepherd, in order to save his flock.

§ 11: When the tribunes reach the place called 'Cowherd's Place' (ta Boukolou, τὰ Βουκόλου), where saint Mark the Evangelist had suffered martyrdom, they are seized with fright by Petros' unnerving bravery in the face of death. When he requests a little time in order to enter the tomb (ἐν τῷ τάφῳ) of Saint Mark and pray, they grant his wish provided that he not delay.

§ 12: After Petros descends (κατελθὼν) into the tomb and embraces Saint Mark's grave (τὸν τάφον), he sees the Evangelist in front of him as though sitting there and speaking to him. He prays to the saint, calling him first bishop of the throne [of Alexandria], who preached the Gospel to all Egypt and the boundaries of the city, and finally achieved the crown of martyrdom. He enumerates the Evangelist's successors: 'Anianos ... Melios and so on, then Demetrios and Herakles, and after them Dionysios and Maximos and blissful Theonas, who raised me'. He asks the saint to pray for him to complete his martyrdom with unwavering heart. He commends his flock to the saint, who had originally entrusted it to his predecessors.

§ 13: Rising to his feet, Petros lifts his hands heavenwards and prays for God to end the persecution and to make his martyrdom its 'seal'. Meanwhile, a holy virgin living a life of ascetic seclusion in her own villa (προάστειον) near the tomb of Saint Mark, hears a voice from the heavens saying 'Petros the beginning of the apostles, Petros the end of the martyrs'. Having finished his prayer and kissed the tombs of saint Mark and the other holy bishops buried there in front of him, Petros comes up from the tomb. The tribunes, seeing his face radiant like that of an angel, are too afraid to speak to him. At the same time, an old man and an old virgin woman happen to pass by on their way to sell their wares – skins and cloth – in the city. Petros realises this is God's plan, makes the sign of the cross and, questioning them, learns they are Christians and on their way to the city. He asks them to wait a little, and they oblige him, recognising at once their archbishop in the morning light.

§ 14: Petros tells the tribunes to perform their task while it is still morning. They take him to the valley where the tombs are, 'south of' (ἐκ νότου BHG 1502a, spelled νώτου in BHG 1502) the martyrium of saint Mark. The archbishop tells the old man to stretch the skins and cloths out upon the ground. He then steps on top of them, turns towards the east, kneels thrice and lifts his hands to the sky, thanks God and makes the sign of the cross and bares his neck to the sword, urging the tribunes to do their duty. The tribunes, however, are frightened and none of them dares lay a hand on the saint. They finally agree to give each five gold pieces so that the one who dares to do the deed will take the gold. One of them lays out twenty-five gold coins, giving the twenty as a loan to his comrades. Finally, one is selected by lot for 'the lot of Judas', and cuts off the archbishop's head on 25 November (BHG 1502 adds the Egyptian date, 29 Athyr). The killer taking the gold, they all flee, fearing the crowd. The body remains in place, standing upright, for hours before the crowd guarding the prison is informed.

§ 15: When the people camped at the prison entrance learn of the events, they run to the place and find the old man and woman guarding the body. They lay it down upon the sheets of cloth as though on a bed and wipe off the blood, weeping. All the people of the city mourn. The 'first citizens' (οἱ πρῶτοι τῆς πόλεως) wrap the body in the skins and secure it, because the people have started ripping off bits of Petros' episcopal garments, threatening to leave the body bare.§ 16: There is a great uproar as the people are divided into two factions, the one wanting to take the martyr's body to the 'Place of Theonas' (τὰ Θεωνᾶ) [presumably indicating the church of Theonas, for which see Discussion] where he had been raised, the other insisting that he be buried at Saint Mark's where he had been martyred. Fearing a conflict, certain people belonging to the first faction (called 'of the Dromos', οἱ τοῦ Δρόμου) snatch the body and take it away on a boat past the Pharos, through the so-called Leucas, and bring it to the cemetery which Petros himself had built in the western suburbs. Even so, the mourning crowd which now flocks to the cemetery will not allow them to bury the martyr before they have first brought him into the church [lit. to the holy altar, ἐν τῷ ἁγίῳ θυσιαστηρίῳ] and seated him upon his own throne as though he were alive.§ 17: The people had the following reason for doing this. For some time, the archbishop had not sat upon his throne during the liturgy, but would ascend as far as the podium of the throne, say his blessings, and then sit on the footstool of the throne. The people resented this, and on one occasion had become angry and shouted at him to sit on his throne. The archbishop had then managed to persuade the people to calm down, and had once again sat on the footstool. Afterwards he had rebuked the clergy for taking the people's side in trying to persuade him to sit on the throne, and revealed to them that the reason for his strange behaviour was that he could see an ineffable force, resembling light, upon the throne, and, fearful of sitting there himself, would sit on the footstool as a compromise.§ 18: Thus, on this occasion, the priesthood dons the vestments of their rank and seats the martyr's body upon the throne; and afterwards the entire congregation addresses the martyr, saying that, even if in life he had not wished to sit upon the throne, now when consummated with Christ he has finally sat on it even if unwilling. They then ask him, the 'holy Pope of God' (ἅγιε τοῦ θεοῦ πάπα) to act as intercessor on their behalf. After this, the bishops take holy (ὅσιον) Achillas, make him stand close to the throne, and put the martyr's omophorion on his shoulders. Achillas gives an encomiastic speech in honour of the hieromartyr Petros, and then proceeds to perform his burial rites. The people bring linen and silk cloths and perfumes, and they bury the martyr with all honours in the cemetery which he himself had built. Even until today many miracles (σημεῖα, 'signs') take place there by the grace of Christ, for as in life, even more so in death the martyr takes care of his people and intercedes on their behalf with God.Text: Viteau 1897, 69-83 (BHG 1502) and Devos 1965, 162-177 (BHG 1502a). Summary: N. Kälviäinen.

Analysis

The Greek Martyrdom of Petros of Alexandria survives today in two versions, the more concise BHG 1502 and the slightly more extensive BHG 1502a. In the main, the two versions transmit the same text, the differences being seemingly a matter of a more condensed expression in 1502, especially the beginning (§§ 1-3), the content of which is only briefly summarised in BHG 1502. In most cases, BHG 1502a seems 'fuller' and in most if not all cases probably transmits a more original text (one likely explanation being that BHG 1502 has undergone abbreviation at some point), but in any case there are few if any differences in essential details. Our summary is accordingly based on 1502a. For the manuscript tradition of the text, see

http://pinakes.irht.cnrs.fr/notices/oeuvre/17548/. There is known to exist a Latin translation of BHG 1502a by Anastasius the Librarian (9th c.), which has been identified by Devos as the text listed as BHL 6698b, while another extant Latin text (BHL 6692-3) is attributed by Devos to Guarimpotus, another 9th c. translator (Devos 1965, 158-159).

The transmission of the Martyrdom in various languages has been studied by Telfer (1949). His comparison of the extant Greek, Latin and Arabic versions enabled him to distinguish two recensions, a 'short' one and a 'long' one, both of which are summarised separately in Arabic by Severus ibn al-Muqaffa, a 10th c. Coptic bishop of Hermopolis (el-Ashmunein). The short recension, which, apart from Severus' summary, is only preserved in the Latin text published by Surius in 1575 (BHL 6696, see Telfer 1949, 119-121) ends with Peter's execution in or at his cell immediately after the executioners have opened the hole in the wall (i.e. it contains §§ 1-10 in Devos' edition and our summary). The long recension, on the other hand, has Peter die only after first visiting the shrine of Saint Mark (§§ 11-14). In addition, the summaries of the long version by Severus and the Copto-Arabic synaxary, as well as the Syriac version, do not include §§ 15-18 (the confusion surrounding the fate of Peter's body and his eventual burial, including the consecration of Achillas as his successor), which are only present in the Greek BHG 1502-1502a and its Latin translation by Anastasius, as well as the Ethiopian version; these last versions, which contain §§ 1-18, are therefore called by Vivian (1988, 66) the 'longest' recension. For an analytic list of all the known versions of the text in different languages, see Vivian 1988, 67-68.

As is evident from our summary, the extant Greek versions BHG 1502-1502a both transmit the longest recension. The main question with respect to the different recensions is, of course, their respective chronological order. According to Telfer's analysis, the short recension must be considered the more original form of the Martyrdom due to its greater historical accuracy, whereas the longer version (or versions, as per Vivian) is due to a later redactor(s) seeking to embellish the legend and supplement it by the addition of local Alexandrian traditions, such as tying Peter's martyrdom to the cult of Saint Mark the Evangelist (Telfer 1949, 118-122 and Vivian 1988, 66-68). Telfer argues that the hagiographer who composed the original Martyrdom had recourse to a historical source which supplied him with information about past bishops of Alexandria. He identifies this source with the so-called 'Jubilee book', a historical work composed in 368 to celebrate the fortieth anniversary of Athanasius I as bishop of Alexandria, and proposes that it was later used, in Latin translation, by Anastasius the Librarian who drew on it for further information to add to his above-mentioned translation of the Martyrdom of Peter (Telfer 1949, 117-118 and 122-130). In his article (1949, 126-130), Telfer collects those sections of the Latin texts of Surius and Anastasius which to him seem most likely to derive from this source, thus giving an idea of its contents, but it must be noted that these are intended by Telfer as fragments of the Latin translation of the 'Jubilee book', not the Martyrdom of Peter, and they do not constitute a 'reconstructed Ur-text' of the latter, as erroneously claimed by Vivian (1988, 65 and 67-70).

Telfer's analysis is persuasive at least as far as the fundamental point about the chronological priority of the short recension is concerned, but has not gone completely unchallenged (see Vivian 1988, 66). The question cannot therefore be considered completely resolved, which makes dating the text even more precarious. A certain terminus ante quem for its composition (including the material only contained in the long version) is provided by the Syriac translation, which survives in a 7th c. manuscript (Telfer 1949, 119; see E0XXXX); Telfer further suggests that the long version predates the Arab invasion (Telfer 1949, 118-119). In addition, the text is quoted by Justinian I in 540 in his Tractate against Origen (Telfer 1949, 119), meaning that the short version at least must derive from the early 6th century or earlier, but probably not before the late 4th (cf. Telfer 1949, 124 n. 1). A more precise date is not possible to establish with certainty, but one might be tempted to connect the phrase about the schisms caused by Origen still causing turmoil in the church (in § 8) with the so-called 'first Origenist crisis' which was a source of unrest in Egypt in 399-403, when the patriarch Theophilus threw his weight behind the anti-Origenist faction amongst the monks, and persecuted the Origenist monks of Nitria. It is not inconceivable that the first version of the text would have been written during these events, or when their memory was still relatively fresh.

DISCUSSION

Although clearly written long after the protagonist's death and not a very reliable source for the events it purports to describe (cf. Vivian 1988, 64), the Martyrdom is an important witness to later cultic practice and the ecclesiastical topography of Alexandria. Peter is presented as praying at the tomb of saint Mark, which is said to be located in Boukolou, a site in the eastern part of the city close to the shore (McKenzie and Reyes 2007, 240; Pearson 1986, 153-154). From the description of this scene in §§ 12-14, it is apparent that the shrine of Saint Mark consisted of a church building, a martyrion (μαρτύριον), inside which there was an entrance to an underground crypt in which were located the 'graves' (τάφος, μνῆμα) of Mark and the past bishops of Alexandria, probably in the form of sarcophagi. To the south of the martyrion there was a valley 'where the tombs are' (εἰς τὴν κοιλάδα ὅπου τὰ μνημεῖα). Cf. also the (possibly 5th century) martyrdom account of Saint *Mark the Evangelist (E06893), which also mentions the church at Boukolou and the preservation of Mark's relics in 'a carved space' (ἐν τόπῳ λελατομευμένῳ, presumably a reference to the same underground crypt visited by Peter).

Another prominent element apparently featured in the text (§§ 16-18) is the 'church of Theonas', his immediate predecessor, which is usually understood to have been located in the western suburbs of Alexandria (McKenzie and Reyes 2007, 240; Pearson 1986, 152). The text is not always entirely explicit about the identification of the various locations referred to, but it is usually assumed (cf. Vivian 1988, 47) that this is the 'place of Theonas' (τὰ Θεωνᾶ), where the faction of the Dromos (a quarter of the city) want to take Peter's body, and the place where it is actually taken when the Dromites finally seize it and take it away by boat. (Since Saint Mark's shrine is to the east of the city, near the sea, the quickest and safest way to transport Peter to a suburb on the other side of the city is of course by boat, past the Pharos island.) The martyr's body is then said to have been taken to a western suburb (εἰς τὸ δυτικὸν τῆς πόλεως μέρος ἐν τοῖς προαστείοις), to a cemetery (κοιμητήριον) which Peter himself had built. However, the people do not allow him to be buried before the ceremony described in §§ 17-18, through which episcopal authority is officially transferred to the new bishop, Achillas, in a (presumably nearby) church which must have been considered the city's cathedral, the official seat of the bishop, since according to the text, Peter's body is seated 'on his own throne' (ἐν τῷ ἰδίῳ θρόνῳ). This is presumably the church of Theonas, and possibly the very church where he is said to have been arrested in the first place, thus completing a geographic as well as a narrative circle. It has also been argued that the description of Peter's funeral and Achillas' consecration as bishop in his stead may to some extent echo actual Alexandrian traditions, at least as far as the transfer of the omophorion to the new bishop is concerned (Vivian 1988, 47-49).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Editions:

Devos, P., "Une Passion grecque inédite de S. Pierre d'Alexandrie et sa traduction par Anastase le Bibliothécaire", Analecta Bollandiana 83 (1965), 162-187. (BHG 1502a, together with the the 9th cent. Latin translation of Anastasius, BHL 6698b)

Viteau, J., Passions des saints Écaterine et Pierre d'Alexandrie, Barbara et Anysia (Paris 1897), 69-83. (BHG 1502)

Further reading:

McKenzie, J. and Reyes, A.T., "The Churches of Late Antique Alexandria: the Written Sources," in: J. McKenzie, The Architecture of Alexandria and Egypt, c.300 B.C. to A.D. 700 (London, 2007), 240-242.

Pearson, B.A., "Earliest Christianity in Egypt: Some Observations," in: B.A. Pearson and J.B. Goehring (eds.), The Roots of Egyptian Christianity (1986), 132-159.

Telfer, W., "St. Peter of Alexandria and Arius," Analecta Bollandiana 67 (1949), 117-130.

Vivian, T. St. Peter of Alexandria: Bishop and Martyr (Philadelphia, 1988), 40-50 and 64-78 (including English translation).

CONTINUED DESCRIPTION